We begun to study extra-personal space integration mechanisms by developing decisional mechanisms, in order to define minimal required information that a space memory must provide.

The selected mechanism is based on the following assumption: as the agent tries to enact interactions with positive valences, it is interesting to move closer to elements that afford such interactions. We thus propose that the decisional mechanism adds a positive utility value to interactions allowing to move closer to elements affording interactions with positive valences, and a negative utility value to interactions allowing to move closer to elements affording interactions with negative valences. Elements affording interactions are recognized through signatures of interactions learned by the agent. We must take the estimated distance of elements into consideration, so that close elements have a greater influence on agent's decisions. Thus, the space memory must provide two types of information about surrounding elements: an estimation of their distances and interaction(s) allowing to move closer to these elements.

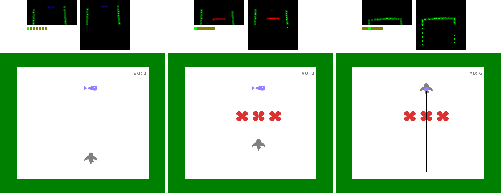

First tests were conducted on a simulated agent with a visual system that can detect three colors (red, green, blue) with a visual field of 180°. The agent is based on the parallel version of the Radical Interactionism Model (called Parallel Radical Interactionism, or PRI). The visual system provide a set of secondary interactions associated to visual stimuli. We used a hard-coded space memory that store and update position of visual interactions relative to the agent when it is moving, during nearly ten cycle of decision. This memory adds to interactions considered as enactable a utility value that depends on distance variation of objects, relative to the agent, that they produce, and that is added to valences of interactions. The decisional mechanism then select the enactable interaction with the greatest ''extended'' valence (see Gay, Georgeon, and Wolf 2014, and Gay 2014 for more details on the implementation).

Preliminary tests have shown that, like peri-personal mechanisms, learning signatures is needed to ensure that the agent will not generate behaviors based on wrong or incomplete signatures that it couldn't revise. We added a learning mechanism that forces the enaction of an interaction when the certitude of its prediction of success or failure in the current context is lower than a certain threshold. There are thus no separated learning and exploitation periods, the agent keeps its learning abilities during its entire ''life''.

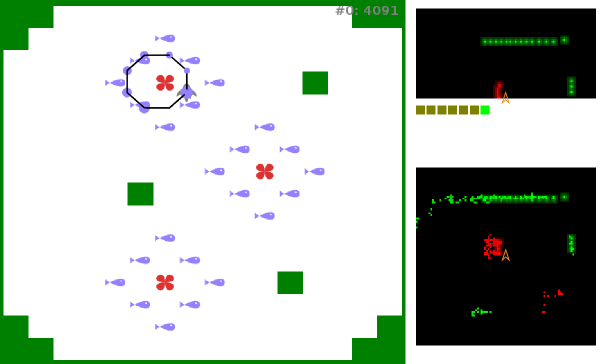

Experimental tests have shown that signature learning is relatively fast: after nearly 2000 decisional cycles, the agent rarely uses learning mechanism, and is mainly directed by the exploitation mechanism. The agent move toward food and avoids walls. We then conducted several experiments to test the decisional system.

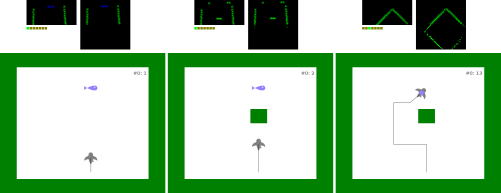

Tests were conducted to analyze how the agent ''interprets'' its environment. We use the fact that the agent is strongly attracted by preys to observe how it reacts in presence of other objects. It appears that algae, that have the same interactional properties as empty space, became ''transparent'' for the agent. In contrast, the agent stays away from walls.

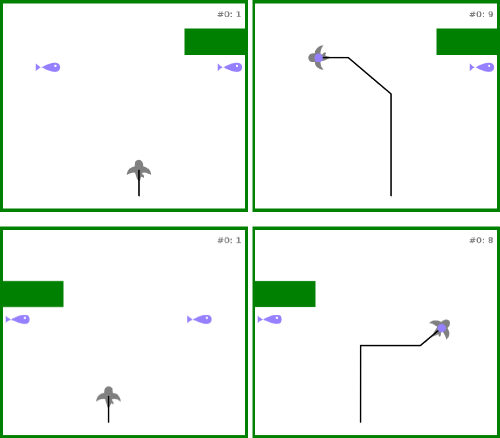

We also observe that the agent takes every elements of its environment into consideration. In presence of two prey placed symmetrically, the agent will move toward the one that will seems less ''dangerous'' to reach. Here, the prey that is far from walls.

In this last experiment, preys are invisible, and stay at the same distance from an alga. After learning signatures, we observe that signature of interaction ''eat'' is characterized by the presence of a red object at a certain distance. This results a behavior where the agent turns around algae to eat preys, even if they are invisible. This example shows that signatures of interactions do not only consider the affordance itself, but also surrounding context.

The decisional mechanism is robust enough to be implemented on the ErnestIRL robot, with similar results.